Nikos Mantzaris was quoted in an article by Energy Monitor investigating the challenges associated with Greece’s transition away from lignite both at the national as well as the regional level.

The article was published in Energy Monitor on December 14, 2020 and was titled:

The full article follows.

Greece’s ambitious plans to exit lignite make it a front runner among coal regions in Europe, but its energy transition must avoid creating new stranded assets in natural gas while ensuring economic and social benefits.

By Heather O’Brian 14 Dec 2020

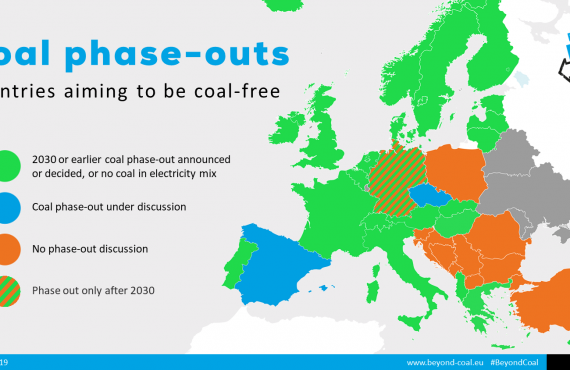

Germany, Europe’s largest economy and long considered a leader in the energy transition, aims to close its last coal-fired power plants only by 2038. Hard hit by the global financial crisis and an ensuing sovereign debt crisis, Greece plans to cease burning coal for power a full decade earlier. All but one of its coal power plants are set to shut in the next three years.

Greece’s pivot away from coal, announced by Prime Minister Kyriakos Mitsotak at the UN Climate Action Summit in September 2019, was unconceivable just a few years ago.

“The Greek economy has been so reliant on coal and coal has been so firmly positioned in the politics of the country, similar to the situation in Poland, that it was one of those things that you hoped for but didn’t seem possible,” says Mahi Sideridou, managing director of the Europe Beyond Coal coalition.

“Greece’s coal phase-out is ambitious and it is also extremely important because it involves lignite,” says Charles Moore, the European programme lead for Ember, a think tank. “Lignite is dirtier but it is also generally more difficult to move away from because it is cheaper and supports lots of local jobs.”

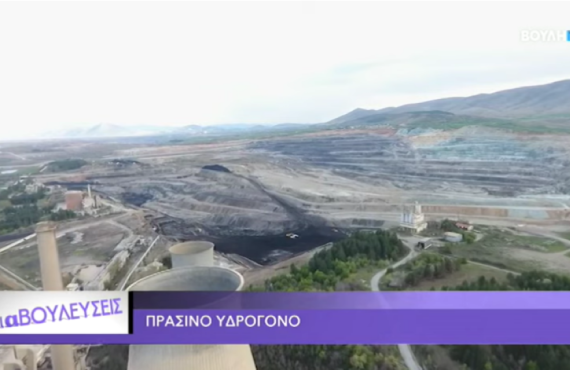

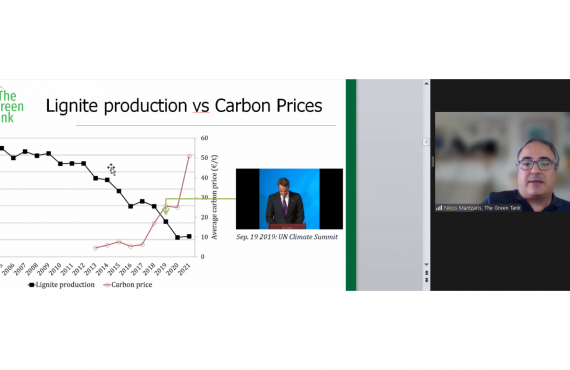

The importance of lignite in Greece’s power mix has been declining for years, although in 2018 it still provided about one-third of electricity. That figure decreased to roughly 10% in the first ten months of 2020. From 1990 to 2017, lignite was also responsible for 34% of the country’s greenhouse gas emissions.

The primary reason for Greece deciding to get off coal is economic. Greece’s state-controlled Public Power Corporation, which operates the country’s lignite power plants, has been losing money on these facilities for years.

“Greece’s lignite is the poorest in the EU by far, and so the most vulnerable to any changes with a financial impact,” explains Nikos Mantzaris, senior policy analyst and partner at The Green Tank, an environmental think tank. “It has the lowest thermal content and so you need to burn more, which means there is more carbon dioxide, and with carbon dioxide prices rising it was the end of the game.”

The Greek government has pledged to cease operations of roughly 3.4GW of operational lignite power plants by 2023. It will also stop burning lignite at the 660MW Ptolemaida V power plant in Western Macedonia, slated to come online in 2022, by 2028, when it will be replaced by another fuel, likely natural gas.

A peak into the future

A glimpse of what a post-lignite future might look like was seen earlier this year. On 8 June, Greece’s power demand was met without any lignite for the first time in 64 years and, on 14 September, renewables covered a record 57% of electricity demand, with wind energy alone accounting for 40% of the total.

Greece’s national energy and climate plan (NECP), updated in December 2019, foresees renewable energy accounting for about 61% of gross electricity consumption by 2030, up from about 29% today. Wind capacity is forecast to rise to 7.05GW and solar photovoltaic (PV) to 7.66GW compared with 3.6GW and 2.8GW, respectively, in 2019.

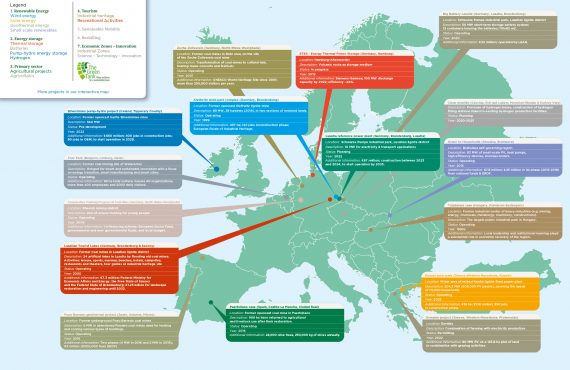

BloombergNEF (BNEF) says Greece has the potential to position itself as a leader in the energy transition in the next decade. In a least-cost scenario analysis published in September, it sees Greece adding 10GW of wind and utility-scale solar in the next decade and nearly 4GW of small-scale solar for homes and businesses. Renewables could provide 68% of all electricity in 2030 and 96% in 2050, it forecasts.

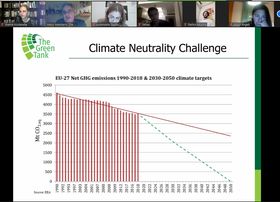

The need for renewable power is set to increase further given last week’s agreement by EU member states to increase the 2030 greenhouse gas emissions reduction target to 55% compared with 1990 levels. E3-Modelling, a Greek energy and environmental consultancy, estimates Greece will need 83–88% of gross electricity to come from renewable sources in 2030, while objectives for renewable energy in heating and cooling and transport will also need to be stepped up.

Encouraged by Greece’s move out of lignite and the country’s strong wind and solar resources, investors are keen on developing projects. French renewable developer Akuo plans to invest close to €1bn over the next five years in Greek wind and solar, including floating solar PV technology, and storage.

Stranded gas assets?

Yet as Europe looks to raise its climate commitment, the role of gas in Greece’s future energy mix is a matter of concern. Greece’s NECP also foresees 1.7GW of new gas-fired power plants coming online in the next decade in addition to the 5.2GW already operating. The new build is necessary to accompany the lignite phase-out and integrate a greater share of renewable energy, says the government.

“Aside from environmental issues, our biggest fear is that a lot of these investments in gas will become stranded assets and result in economic losses, and after transitioning away from coal, we will just have to do another transition in five, ten or 15 years away from gas,” says Dimitris Tsekeris, energy policy officer at WWF Greece.

“The argument is that you will likely need new thermal units to replace coal, but at the moment the risk of stranded assets is high and you should do absolutely anything you can to increase efficiency measures and wind and solar first,” adds Moore.

According to BNEF, it is already cheaper in Greece to source power from new onshore wind or utility-scale solar than building new lignite or gas plants. By 2025, it expects new renewables to also be cheaper than running existing gas plants in the country.

Greece is already nearly halfway towards the gas-fired power plant capacity goal laid out in its NECP. A 826MW combined-cycle gas turbine power plant is being built by the Greek company Mytilineos in Agios Nikolaos Viotias in central Greece and is expected to be operational in 2021. That project received financing from the European Investment Bank, which subsequently changed its lending policy to phase out financing of unabated fossil fuels by the end of 2021.

Alongside planned renewable energy and storage investments, Greece’s Just Transition Development Plan for the country’s lignite regions also “includes a lot of fossil gas”, says Mantzaris. “But in order to succeed, the transition needs to be green.”

A just transition

Despite the health and environmental impacts of lignite, trade unions have long opposed shutting coal plants due to concerns about the effect on employment, and some Greek opposition parties continue to argue against their closure.

Residents appear to be facing the transition with trepidation. A recent survey of 802 people living in lignite regions – Western Macedonia and the Megalopolis municipality in the Peloponnese region – published by the research group diaNEOsis in collaboration with Green Tank showed 71% have negative feelings about the move away from lignite and 87% believe it will have a negative impact on the local economy. Nearly half of respondents, however, saw an opportunity to change the economic development model of lignite regions.

The economic situation in Western Macedonia, Greece’s most important coal region, is already fragile. Unemployment stood at 24.6% in 2019 compared with an already high 17.3% for Greece as a whole, a record for coal regions in Europe. The jobless rate for youth was 53.5%. Energy poverty is also an issue.

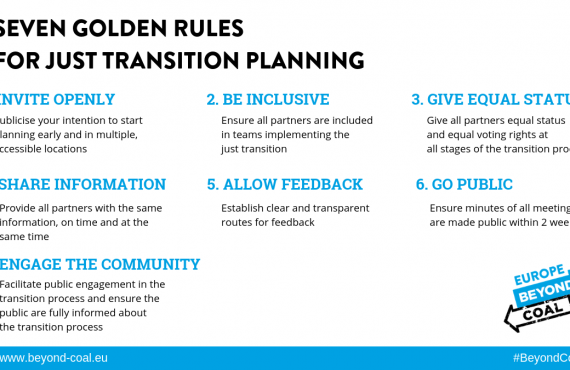

Greek energy and environment minister Kostis Hatzidakis has indicated about €5bn will be mobilised from European and national sources to transform the energy sectors and economies of lignite regions. While the Just Transition Development Plan was put out for public online consultation for 40 days this autumn, the government has largely taken a top-down approach and responses were dominated by non-governmental organisations and think tanks.

The diaNEOsis survey showed more than half of local residents questioned were unaware there was even a public consultation, although about 40% considered the involvement of local communities an important condition for a successful transition.

Jobs will need to be created in other fields, although energy is expected to remain fundamental to the future of lignite regions.

Among headline investments already announced, Greek energy group Hellenic Petroleum plans to invest in 18 solar PV plants with a total installed capacity of 204MW in Kozani, the capital of Western Macedonia. State-owned utility PPC intends to develop 2GW of solar PV plants in Western Macedonia and 550MW in Megalopolis. PPC has also said it could sell stakes in these projects to local residents, allowing them to benefit from the same returns that it expects to make on its investments.

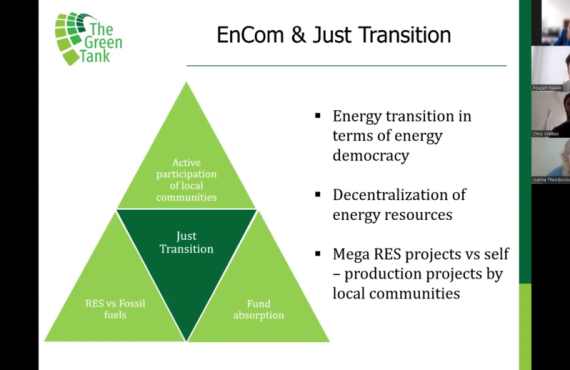

A more inclusive approach to renewable energy projects could help increase their social acceptance, says Michalis Goudis, head of the Thessaloniki office of the Heinrich Böll Stiftung foundation. One way to do this, he says, is by encouraging the development of energy communities, in which people can take an active part and share the economic and other benefits of producing renewable energy.

“Of course you also need big projects, but it is important to be transparent about the way they are being implemented, and that there is a level playing field for everyone,” says Goudis. Large renewable developers are often viewed as being solely interested in profits, with little concern for the environment or people. “You have to convince local communities of the benefits of renewable energy projects and hear their concerns. If things were done properly, we would probably be able to deliver at a faster pace.”

Raising the bar

As Greece races ahead with its coal phase-out plans, laggards like Germany are set to receive the largest share of the EU’s €17.5bn Just Transition Fund. Efforts to introduce a mechanism increasing the allocation of funds to countries that are moving faster, like Greece, have gone nowhere. The five largest recipients – Poland (€3.5bn), Germany (€2.25bn), Romania (€1.95bn), the Czech Republic (€1.49bn) and Bulgaria (€1.18 bn) – together will receive just more than 59% of the total, but all plan to operate coal power plants past 2030. Greece’s allocation is €755m, or 4.3% of the total.

Criteria for receiving funds is based on employment in coal mining and carbon-intensive industries, and industrial greenhouse gas emissions from countries’ carbon-intensive regions. The process doesn’t take into account the compatibility of coal phase-out dates with climate goals, and running coal-fired plants after 2030 is widely seen as being out of step with the Paris Agreement. The Czech Republic’s coal commission aligned with Germany’s unambitious deadline in early December to also recommend a 2038 exit, while Poland, Romania and Bulgaria have yet to set an end date.

“We need to set a good example, so Greece becomes a model for other countries,” says Tsekeris. “This is a colossal transformation and we need to be extremely careful about how we go about it, and be quick and smart and make sure no one is left behind.”